“…too resistless was the delight of staying in the wild hour.”

Dear Reader,

A long time lover of Jane Eyre and the Brontë sisters in general, I was excited to read Villette, Charlotte Brontë’s last novel and one of her more obscure works. It took me a little while to get through the tome, reading other books in between, but I’m glad I read it to the end. There were many passages I found myself reading over and over for their beauty and resonance, and even as I reflect and re-read now, I marvel at how beautifully certain threads weave throughout the story.

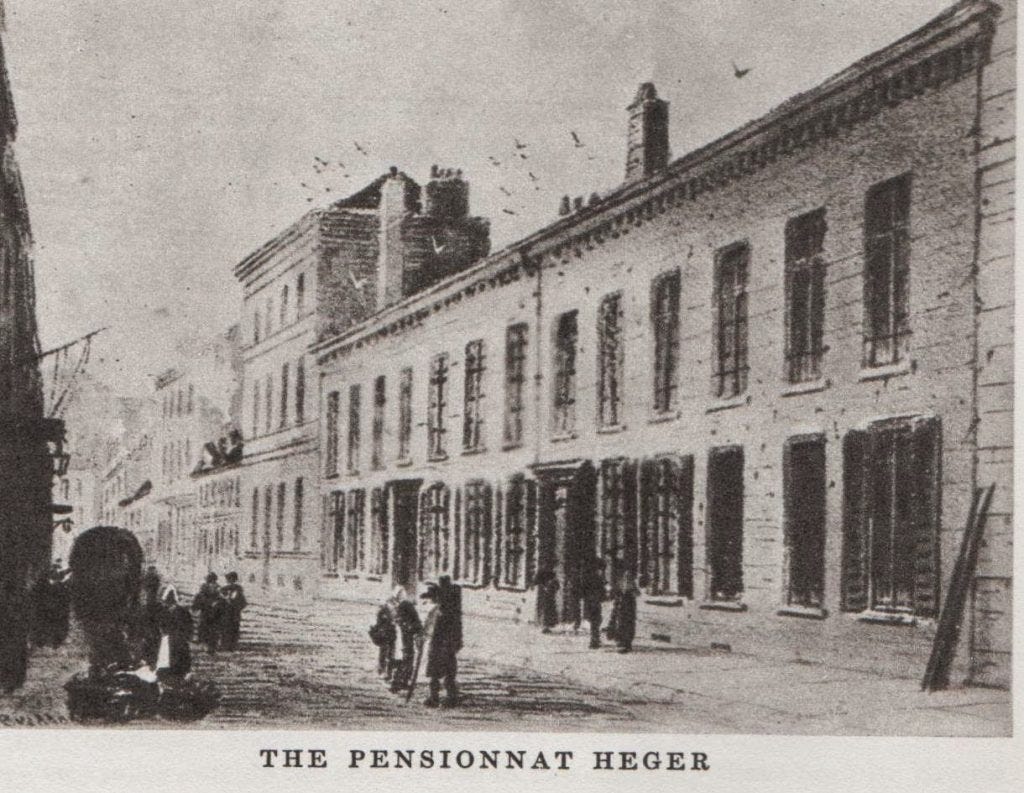

Set in a fictional city (based on Brussels) in Belgium, it is the most autobiographical of Charlotte’s novels. It follows a young woman Lucy Snowe who, after a family tragedy, must make her own way in the world. With the last of her cash and a thin lead on a teaching job, she sails alone to the French-speaking foreign country. Charlotte Brontë herself was a student in Brussels where she battled with unrequited love for one of her teachers. Similarly, in the book Lucy finds a school for girls where she secures a teaching position and also deals with unrequited love. Despite the language barrier and her disdain of the local “Papists” (Catholics), she comes to build a kind of life at the school on the Rue Fosette.

Storm

Lucy, however, still feels the weight of her situation: “About the present it was better to be stoical, about the future—such a future as mine—to be dead. And in catalepsy and a dead trance I studiously held the quick of my nature.” (”Quick” means life.) She describes a time when a bad storm woke everyone at night. She opened her window and stuck her feet out. “It was wet, it was wild, it was pitch dark,” she says, “…too resistless was the delight of staying in the wild hour…” She says storms “woke the being I was always lulling, and stirred up a craving cry I could not satisfy.” [1] The imagery of the thunder and lightning stands in direct contrast to her previous statement only a paragraph earlier about feeling dead. She comes to refer to these warring forces within her as “Imagination” and “Reason”.

The reader never learns exactly what tragedy befell Lucy that took her family, but one can’t help but think of the similar sorrow that the author must have felt. Charlotte Brontë lost her beloved siblings to illness, all within a short time: her two sisters to Tuberculosis and her brother to the effects of an alcohol and opium addiction, all within the span of eight months. In the book, this sorrow continues to cling to Lucy. There is another instance where such a deep despair comes over her, that she falls physically ill. She cannot sleep. When she finally does, she has a horrific nightmare and she wakes up wishing for death. She attempts to pray, but all that can manage are a few lines from Psalm 88: “From my youth up Thy terrors have I suffered with a troubled mind.” [1] Again, there is a crashing storm. This time, Lucy ventures out into the night.

She takes shelter in a church—a Catholic church. The priest who is there shows her kindness and listens to her troubles. Lucy spurns his attempts to turn her to Catholicism, but is grateful for his company. (It is worth noting that, while Lucy disdains its practices throughout the book, she often has good experiences with Catholic characters, eventually coming to the conclusion that Catholics and Protestants share the most important things in common. This conclusion is especially interesting considering that Charlotte was the daughter of a Methodist minister.)

Shadow

This idea of being inhibited is threaded throughout the book in various ways. Lucy frequently describes her clothes: a simple grey dress of functional fabric, a “gown of shadow.” [1] Monsieur Paul, a friend of Lucy’s, is always commenting on any stitch of color she wears other than grey, teasing her. Later on, another character calls Lucy an “inoffensive shadow”—much to her offense. These instances combine to create an impression of Lucy’s meekness. At the school, Lucy befriends a student named Ginerva Fanshawe, a girl who proves to be a perfect foil: vivacious where Lucy is reserved, colorful and bright where Lucy is grey. Ginerva serves to highlight Lucy’s “greyness” both for the reader and for Lucy herself.

Lucy might be figuratively haunted by an unknown past, but she is also literally haunted by a ghost! There was once a nun who died tragically and is buried in the school’s garden, so the tale goes. Though much tamer than the Gothic Jane Eyre, the ghost is the one mystical element in Villette. Here, it functions as a metaphor for Lucy’s fears. The nun is the personification of Reason: buried in the ground, isolated in an ascetic, monastic life, veiled and thus all individuality erased.

Women and Art

At one point in the story, Lucy visits an art gallery with some cousins. On most of the supposed masterpieces she looks with distaste, for they carry not enough realism for her. Then she comes upon a large portrait of Cleopatra depicted as a scantily clad, obese woman reclining on a sofa. Lucy views this painting with similar distaste, though it's not based on a lack of realism but her idea of what the woman in the portrait should be like. For example, Lucy decries the size of the woman, the fact that she is lounging instead of working, and the revealing nature of the subject’s dress.

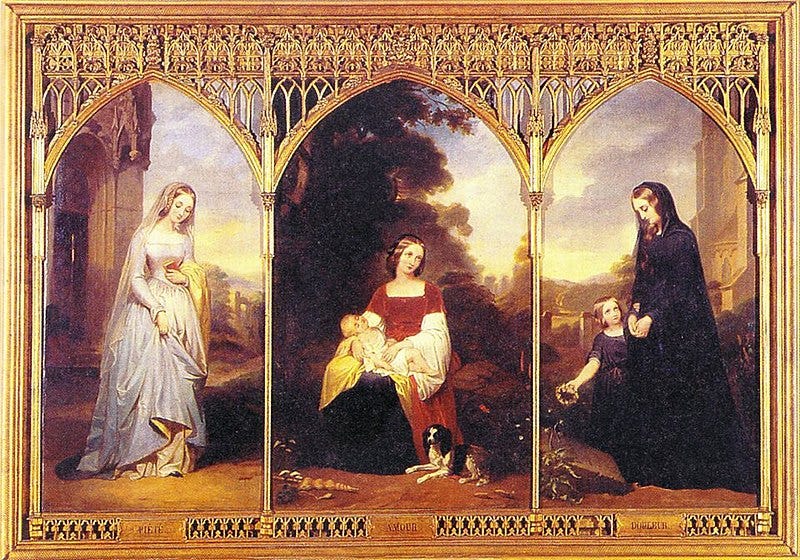

Her friend, Monsieur Paul, then arrives and leads her to another set of paintings, this time a set of portraits titled “La vie d'une femme.” These portraits depict women in different stages of their lives: a young woman, a bride, a young mother, and a widow. They appear to be normal 19th century women. However, Lucy views them, not as the perfect image of reason, but as odious. “Ugly pictures!” she calls them. [1]

Some scholars cite Cleopatra's revealing garment as evidence that Lucy is simply sexually repressed. However, if this were the case then Lucy would prefer the sensible portraits she calls ugly because that would be what society tells her is acceptable. This is not what happens. Lucy disdains many aspects of Cleopatra's portrait, not simply her state of undress: the messy state of the room, for example. The image of Cleopatra does defy expectations of 19th century society, though. Here is a woman with power, unheard of during this time. She has enough money to afford “butcher’s meat” and other rich food; she can rest in the middle of the day and does not need to tidy her own room. Lucy rejects this portrait of power, and yet the two pieces of art act as those opposing forces she has been caught between: Imagination and Reason.

Soon after, Lucy visits the opera. During this time period, people attended concerts and plays, but opera singers, ballet dancers, and actors were not considered part of respectable society. Considering this fact and Lucy’s opinion of the portraits in the gallery, the way that she views the opera singer is surprising. In her mind, she compares the singer to Queen Vashti in the Biblical book of Esther and spends nearly two pages describing her and her performance: clad in crimson (note the contrast to Lucy’s grey), “Vashti” is regal and strong, a “stage empress.” The singer’s character is faced with pain, and she not only bears it, she conquers it: “To her, what hurts become immediately embodied: she looks in it as a thing that can be attacked, worried down, torn in shreds…before calamity she is a tigress…Wicked, perhaps, she is, but she is strong.” [1] In the opera singer, Lucy sees another foil to herself: someone who is free to feel (as Reason, in a later imaginary conversation, tells Lucy she cannot do) and who has mastered her misery.

What’s more, the performance appeals to Lucy’s imagination, and she feels stirred by it: “The strong magnetism of genius drew my heart out of its wonted orbit; the sunflower turned from the south to a fierce light.” Lucy’s companion at the opera and love interest, Dr. John, has a completely different reaction to the singer’s performance. It is clear that he does not feel as deeply nor is affected as much as Lucy. In fact, when she asks him about his opinion afterwards, Lucy says that “he judged her as a woman, not as an artist: it was a branding judgment.” [1]

Patriarchy?

Much of the scholarship surrounding Villette centers on the oppression of women in the 19th century. There is no doubt that women were limited during that time: they were not free to own property, to inherit, or even to own their own bodies and children once married. The number of professions suitable for an unmarried woman were few and far between—essentially, one could be a teacher at a girls’ school or a governess. In her time, Lucy Snowe was not free to move about in the world as a man. Scholars tend to use this historical reality to focus on Lucy’s supposed sexual repression or her “internalize(d) destructive strictures of patriarchy.” [2]

The blunder of this analysis, however, lies in that it does the very thing that Brontë herself despised: it judges the woman instead of the artist.[3] Certainly, Lucy’s womanhood contributed to the limitations of her situation and her choices in life, but a more faithful reading of the story would consider the deep sorrow that Lucy feels so keenly throughout the book. Like the author, she faced great personal loss, and that is the root of her isolation and despair. Lucy may appear meek and mild, but her inner life is that of storm. She feels limited and tied down by Reason, due to her situation as a whole—her womanhood, her poverty, and her lack of family, and her pain—not simply due to her womanhood.

Hope

Did Charlotte Brontë feel the same sorrow in the latter years of her life? Was she plagued by the storm of her imagination and dreams, forever tethered by reason and her position in life? We know that she indeed felt limited by the way that people viewed her as a woman author, and she was no doubt weighed down by being the only surviving sibling. Perhaps we may find a clue to the author’s life in the pages of Villette. The resolution is somewhat open-ended. In the climax of the novel, Lucy ventures out into the streets at night, Similar to the beginning of the novel, but this time she is met with crowds of people. There is a religious festival going on, and at midnight the streets of Villette are teeming with people. This scene presents a very different portrait than her earlier wandering: no longer is she isolated in vacant streets, but she is with a community, a part of a whole.

We don’t get the true happy ending we do with Jane Eyre. I won’t give it all away, but Lucy achieves one of her dreams: opening a school. And the novel ends with yet another storm. This time it is possibly bringing Lucy another one of her desires, though we never find out for certain. Perhaps this is because the author, herself, felt as though her own ending was yet to be discovered—and yet the novel ends with a distinct sense of hope, which can be summed up best in the words of Lucy herself: “I believe that this life is not all; neither the beginning nor the end. I believe while I tremble; I trust while I weep.”

[1] Charlotte Brontë, Villette (New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2005).

[2] Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (London: Yale University Press, 1979), pg. 399–440.

[3] Anna E. Clark, “Charlotte Brontë’s Anger,” Public Books, June 23, 2020, https://www.publicbooks.org/charlotte-brontes-anger/. “To you I am neither man nor woman. I come before you as an author only. It is the sole standard by which you have a right to judge me, the sole ground on which I accept your judgment.” –Charlotte Brontë

Join the conversation

If you’ve read Villette, what did you think? What Brontë sister book should I read next?