Songs of Creation: In the Beginning Tolkien and Lewis Created Narnia and Middle-earth

What The Silmarillion and The Magician’s Nephew teach us about Middle-earth, Narnia, and our own creations

Dear Reader,

This week I have a special treat for you! We have a guest post from JRR Jokien from Jokien with Tolkien. I love creation themes here at Midnight Ink, so I am especially excited for you to read this wonderful examination of works by two of my favorite authors, Tolkien and Lewis.

Neighboring Pools in The Wood Between the Worlds

Narnia and Middle-earth would surely be neighboring pools in the Wood Between the Worlds, the fantastical realm from The Magician’s Nephew that connects myriad worlds and enables travel between them. Like the authors who created them, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, Narnia and Middle-earth are similar in many key ways, one of which is their creation stories.

Lewis and Tolkien were both Christians who believed in a God who in the beginning created the heavens and the earth. They were also authors who would go on to create their own heavens and earths in creation accounts that share striking similarities. Since they were both familiar with the Biblical creation accounts and each other’s work, it is instructive to compare and contrast the creation accounts that they themselves composed and the Biblical narrative that informed their thinking as well. Doing so perfectly illustrates Tolkien’s concept of “sub-creation” and the ways that each individual creator brings their own power of creativity to bear on their creations.

The Music of the Ainur

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion begins with the tale of the creation of Arda, the world containing Middle-earth. The key instrument in this creation is music.

In the opening chapter, “Ainulindalë,” Tolkien describes how Eru Ilúvatar, the One, created angelic beings known as the Ainur. Ilúvatar gives to them a mighty theme and the Ainur sing a Great Music along this theme. While the theme is Ilúvatar’s, the actual music is the Ainur’s. They each bring their own character and talents to the theme, adding to it in harmony with each other and with Ilúvatar’s intent for it.

But the harmony does not last for long.

The greatest of the Ainur, Melkor, decides to add his own theme to the music in discord with the theme of Ilúvatar. The dissonance grows, and Ilúvatar and Melkor strive for dominance. Ilúvatar introduces a second and then a third theme, which Melkor continues to fight against with his own discord. Finally, Ilúvatar ends the music with one final chord, “deeper than the Abyss, higher than the Firmament, piercing as the light of the eye of Ilúvatar.”1

The Music ceases.

Ilúvatar reveals to the Ainur that the Music has created a new world, and that what they each added to the Music, even including Melkor, has been reflected in the creation and the history of the world itself.

To Melkor, Ilúvatar proclaims though he intended to usurp the music for his own glory, Melkor “shall see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined.”2

Strikingly, we see many similarities in the story of the creation of Narnia in The Magician’s Nephew.

Aslan’s Song

After traveling from England to a dying world with a giant red star named Charn and back to England, a young boy and girl named Digory and Polly find themselves and several others–including a Queen-turned-Witch from Charn and Digory’s uncle–in a world of no stars and no light. Aside from the ground that they stand on there is nothing: no plants, no wind, no animals, nothing.

And then, “[i]n the darkness something was happening at last. A voice had begun to sing.”3 The song is beautiful and transcendent.

Suddenly, innumerable other voices join the First Voice in the song “in harmony with it”4 and simultaneously “the blackness overhead, all at once, was blazing with stars.”5

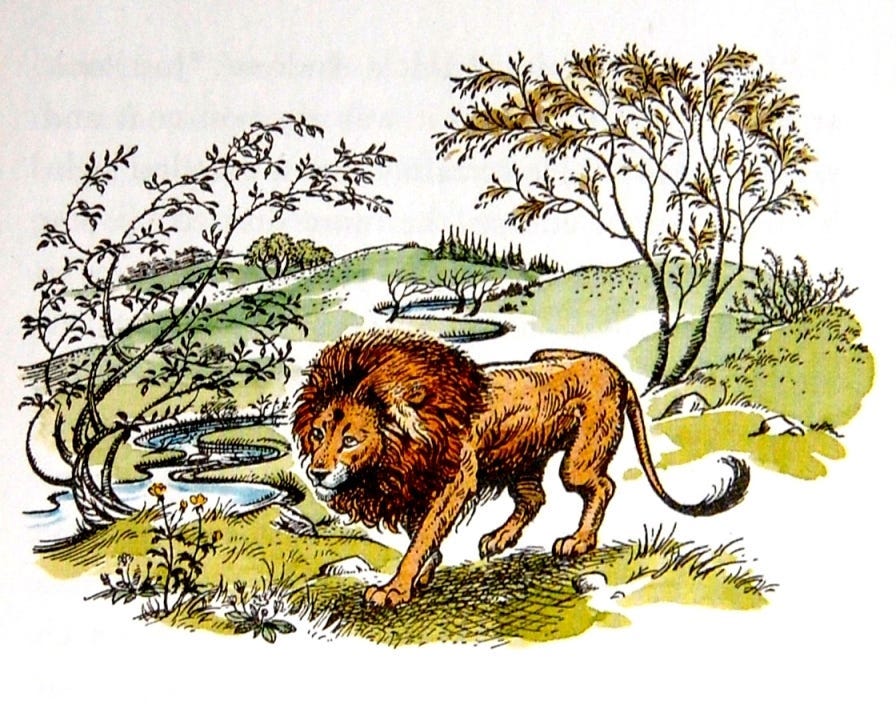

Light breaks and the sun rises. And by the light of the sun, Polly, Digory, and the others can see the Lion Aslan, “huge, shaggy, and bright”6 whose “mouth was open wide in song.”7 The Lion is singing the song of creation.

Aslan’s song proceeds from the initial song through another, gentler movement where he creates vegetation for the world and then a wilder movement where he creates animals. And then the song stops.

Like Melkor’s discord, Evil is already present in Narnia at its creation. Digory has brought the Witch from Charn — who will go on to eventually cover Narnia in an endless winter — into this new world and thus brought evil into it.

Like Ilúvatar, Aslan has a plan to deal with the evil that has entered Narnia. In a parallel of the story of Adam and Eve, Digory is sent to retrieve an apple from the tree at the center of a garden. He is told he cannot eat or take this fruit selfishly, but the witch tempts him to take it for himself with the promise of eternal life for himself and healing for his sick mother. In an inversion of the Biblical temptation account, he prevails.

The apple is planted and grows into a tree that will protect Narnia as long as it stands, and Aslan promises to personally deal with the evil once it comes: “I will see to it that the worst falls upon myself.”8 In contrast with Ilúvatar–who on occasion intervened in the fate of Arda but did not come to Arda physically9 or suffer death on behalf of his children–Aslan would take the worst of evil’s power upon himself and die so that by the Deeper Magic he could defeat evil.

Creators Creating in the Image — But Not Exact Copy — of Their Creator

The creation accounts of Narnia and Arda have many parallels. Both worlds are created through song.10 This song is part of the plan of God and each song has three movements. Evil is present from the very beginning and Ilúvatar and Aslan already have a plan to deal with it.

And yet for all their similarities with each other, they both also have significant differences from the Biblical account of creation in Genesis 1.

Unlike Ilúvatar or Aslan, Yahweh creates the world without any help from or participation by the angels of heaven. Though He creates using the power of his voice, He does so without music.

Evil in Arda in the form of Melkor’s discord introduced as part of the song of creation. Similarly, the Witch is present in Narnia mere hours after its creation. God in creating the world, however, completed His work and pronounced all that he saw “very good” (Genesis 1:31).

In creating worlds like Narnia and Arda, the authors engaged in what Tolkien termed “sub-creating.” In his famous essay “On Fairy-Stories,” he explains:

“Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”11

Part of God saying in Genesis 1:26, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness,” is that humans will create. Tolkien refers to this in fantasy as “sub-creation,” where sub-creators “make a Secondary World which your mind can enter.”12

Just as the Creator created creation, so Tolkien and Lewis as sub-creators fashioned Narnia and Arda. In doing so, they created in the likeness of their Creator but not to the point of an exact copy. Like the Ainur adding their own details to the theme of Ilúvatar, they added their own individual touches to the story they told of the creation of their respective fantasy worlds. To do so, the authors pulled details and inspiration from the primary world, the creation stories of other cultures and peoples, and their own imaginative faculties.

As Christians, we can learn much from those sub-creators who have gone before us. In drawing from the truest fairy story of them all–the gospel13–and from our own lives, experiences, and talents, we too can create in the likeness of our Creator. What will you create? Will you compose a song of your own? Cultivate a garden? Care tenderly for your family? Create your own world that takes its place as a pool neighboring Narnia and Middle-earth in the Wood Between the Worlds? How will you make as one who makes in the image and likeness of your Creator?

If you enjoyed with post, consider subscribing to Jokien with Tolkien or sharing this post with a friend!

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion Illustrated By The Author, ed. Christopher Tolkien (New York: William Morrow, 2022), 5.

Ibid.

C.S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew (New York: HarperTrophy, 1994), 116.

Ibid.

Ibid., 117.

Ibid., 119.

Ibid., 120.

Ibid., 161.

No, as much as I want Tom Bombadil to be the avatar of Ilúvatar, he is not.

Check out Karissa’s wonderful essay on creation themes in The Magician’s Nephew if you haven’t already for great insights like the following on how familiarity with Medieval cosmology might have inspired Lewis (and Tolkien!) in their own creation accounts: ‘As a scholar of Medieval literature, [Lewis] would have been familiar with the concept of the universe that was popular during that period (borrowed from Boethius, which was borrowed from Cicero and Calcidius): the idea that the stars and planets produce their own music, each heavenly body with its own tone, creating a symphony and an order.” Seriously, go read it, it helped inspire this comparison of The Magician’s Nephew with The Silmarillion you’re reading!

J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” The Tolkien Reader (New York: Ballantine Books,1966), 75

Ibid., 60.

“The Gospels contain a fairy-story,” Tolkien contends. “But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation.” Ibid., 88.

Not exactly your point here, but reading your summary of Magician (with which of course I'm quite familiar--but I also haven't reread it in a while) reminded me that there's an inversion of the human/"human" response to temptation in Perelandra, too. And now I'm intrigued that Lewis wrote TWO creation stories in which the temptation is resisted, and I'm curious about what was behind that for him.

The Simarillion is probably my favorite work of Tokiens. I think its facinating how he bleands mythology and his christian views of the cosmos. Many roman and christian monks alike as well as hindu texts have called creation a song and people all over speak of a rhymic or musical structure to life and being. I think tokien was drawing upon that and platonic theories of the world. When writing this but its facinating to see him create a whole world and mythology simply out of langauge.